Despite being perceived as being healthy and doing well in various areas, Asian Americans are facing low levels of health literacy. This means many Asian American subgroups may struggle to obtain and understand basic health information and services needed to make important health decisions.

It is complicated enough for an English-speaking Asian American to navigate the American healthcare system. Who among us can describe all the significant aspects of the Affordable Care Act? What services are considered “preventive health”? Why is it so expensive to get an EpiPen in the U.S. versus Canada?

Throw in limited English proficiency and the problem worsens. Limited English proficiency has been associated with low health status among Asian Americans, Latinos and other racial/ethnic groups.

Next, communication between healthcare providers and Asian American patients is further complicated when coupled with the cultural background differences between Asian American culture and Western culture.

Let’s be clear that the term “Asian American” is broad and encompasses a wide range of individuals from more than 50 countries and more than 30 ethnic groups. The cultural attitudes and beliefs of one Asian culture cannot be perfectly mirrored onto another culture.

Therefore, how can a healthcare team accommodate the diverse spectrum of Asian American patients and engage them in meaningful cross-cultural communication? Below are a few broad suggestions for healthcare providers. *

Focus on the Whole Family

In general, interpersonal relationships and family are highly important among many Asian Americans. They tend to focus on how their condition impacts their family. For some, a disease, such as cancer is seen as a disgrace to the family. Patients with cancer may want to hide their diagnosis from their family.

By understanding the value of family and, potentially, the need for privacy among Asian Americans, healthcare providers can help their patients find appropriate outlets to cope. Depending on the patient’s preference, healthcare providers may say, “Take some time to discuss the matter with your family and decide on a course of treatment,” instead of asking the patient to decide for themselves.

According to Dr. Catherine Marshall, an associate research professor in Frances McClelland Institute of Children, Youth, and Families at The University of Arizona, “It is time that family-focused intervention be made available to families facing cancer.”

Teach-back

Sometimes, healthcare providers may be caught up in delivering the message that they fail to realize their patients are not understanding and retaining the information. They may assume that if a patient is not understanding something, they will ask for clarification.

In some Asian cultures, it is disrespectful to question the authority of the doctor or higher authorities. As a result, some Asian American patients may not ask questions even though they are confused.

A method to ensure understanding and bypass the patient’s discomfort of challenging the provider is the teach-back method. The provider will ask the patient to repeat their care instructions and will provide constructive feedback as necessary.

Non-verbal cues

Approximately 93% of communication is nonverbal (i.e. body language and tone of voice). Individuals raised in a Western society understand a lack of eye contact to be disrespectful and a sign that the other person is not listening.

The opposite is true for some high-context cultures (e.g., China and Japan) where eye contact with a person of higher authority is disrespectful. In addition, smiling and nodding is a way to maintain the harmony and does not necessarily mean the patient understands the provider.

Overall, the same careful considerations should be applied to other forms of communication to the Asian American audience (e.g., brochures, commercials, etc), such as in medical education.

Community Engagement

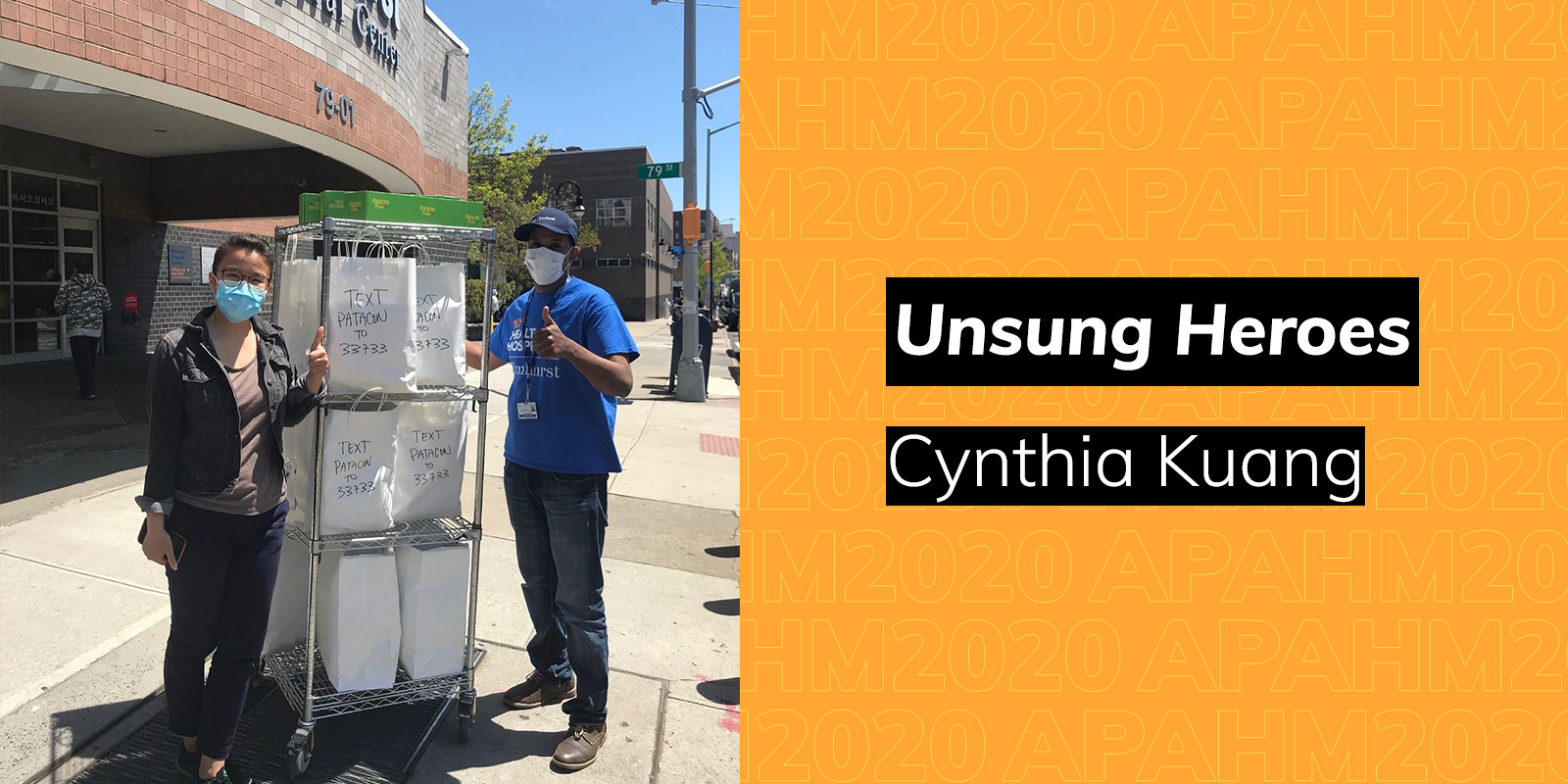

To build trusts between patients and the healthcare team, sometimes healthcare providers will need to step beyond the healthcare facility and reach out to the community they want to serve. A strong starting point is identifying the agents of change in the target community.

These are the people who can help address the issues that are significant to the target community. They may have contacts that the healthcare team does not and may also be from the target community. They may be able to jumpstart difficult conversations, such as regarding sexual health.

Dr. Namratha Kandula is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. She states “the issues that we want to address are…very complex, they are not just about the individual. They are about the social influences, the cultural influences, the environmental influences, and I, as a researcher, cannot know about all of those things for everybody…so it is really about partnering with other people who can teach me…their expertise and I can offer my expertise.”

In the end, to be successful in delivering any message, it is important to know and understand the audience to provide culturally competent care.

Helpful resources:

- Asian American Health Initiative

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum

- AARP Asian American Health Report

- HHS Plans for Asian Americans

- Low Health Literacy

*Not all will apply to every Asian American.